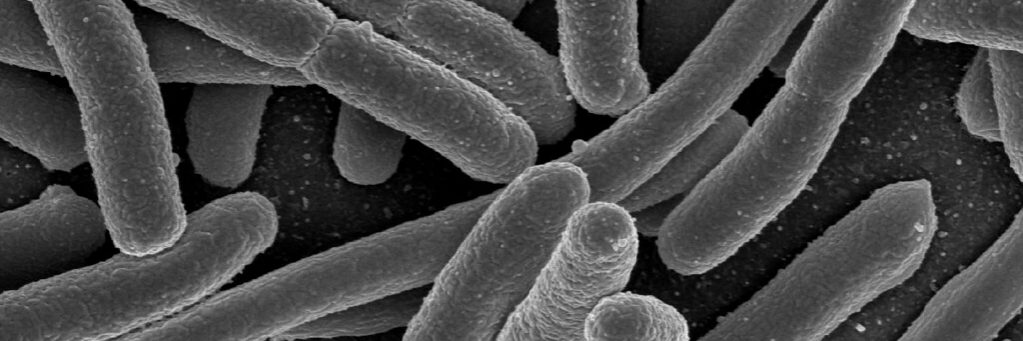

E. Coli and gonorrhoea were two commonly antibiotic resistant bacteria of concern by the WHO. Source: VeeDunn on Flickr

A report by the World Health Organization (WHO) signals that some common bacteria are developing higher resistance to antibiotics, potentially putting “millions of lives at risk”.

The Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) report used data by 87 countries in 2020. It found that high levels of resistance — over 50 per cent — occurred in bacteria that caused common bloodstream infections, particularly in hospitals.

Last-resort antibiotics were used to treat life-threatening infections. But 8 per cent of these surveyed cases reported resistance to antibiotics, significantly increasing the risk of death.

Common bacterial infections also indicated a high resistance to antibiotics.

These include Neisseria gonorrhoea, a common sexually transmitted disease, and E. coli, the most common cause of urinary tract infections. The WHO found over 20% of E. coli were resistant to first and second-line treatments. Gonorrhoea was resistant to one of the most used oral antibacterial treatments in over 60% of cases.

Notable is the global rise in cases of ‘super gonorrhoea’ — those that are highly resistant to typical treatments — in recent years. The most recent high-profile case of super gonorrhoea was this past June in an Austrian man who had returned from Cambodia. In the past decade, every Australian state and territory has detected at least one case of super gonorrhoea.

The WHO considers antibiotic resistant bacteria to be a major global health concern.

“Antimicrobial resistance undermines modern medicine and puts millions of lives at risk,” said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General.

“To truly understand the extent of the global threat and mount an effective public health response to AMR, we must scale up microbiology testing and provide quality-assured data across all countries, not just wealthier ones.”

According to the WHO, most resistance trends have been stable through the past 4 years. But bloodstream infections due to E. coli, Salmonella and resistant gonorrhoea increased by at least 15% compared to 2017 rates.

More research is required to identify the causes of the observed increase in the rate of resistance. This includes whether it is related to increased hospitalisations and antibiotic treatments during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The WHO notes the difficulty in assessing antibiotic resistance, due to poor testing coverage and laboratory capacity, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

To overcome this, the WHO aims to implement greater evidence generation through surveys and improve surveillance.

The full GLASS report can be found here.