Their struggles have been confirmed through the use of satellites to monitor changes in the ice and breeding habitats.

The research has been published online in Endangered Species Research.

Australian Antarctic Division seabird researcher Dr Barbara Wienecke says that for nearly a million years, emperor penguins responded to unfavourable changes in their breeding habitats by moving to new locations.

But recent loss of their fast-ice habitat and record low sea-ice in 2022 and 2023 led to breeding failure in some colonies, according to the division.

Scientists fear these recent events may herald rapidly worsening ice conditions, to which the penguins have limited capacity and time to adapt.

“Emperor penguins need stable fast-ice for about 10 months a year, to breed successfully and rear their chicks,” Dr Wienecke explains.

“If their breeding platform disintegrates before early December, when the chicks still have their downy plumage, it’s likely they will all perish. If it disintegrates before the end of December, chicks without waterproof plumage will die.”

As long-lived seabirds, emperor penguins can cope with disruptive events provided they do not occur frequently, Dr Wienecke says.

“While they can move to new breeding areas, they have limited potential to adapt to accelerating environmental change and a shorter fast-ice season, as they cannot shorten the time chicks need to grow and develop,” she says.

SATELLITE IMAGES

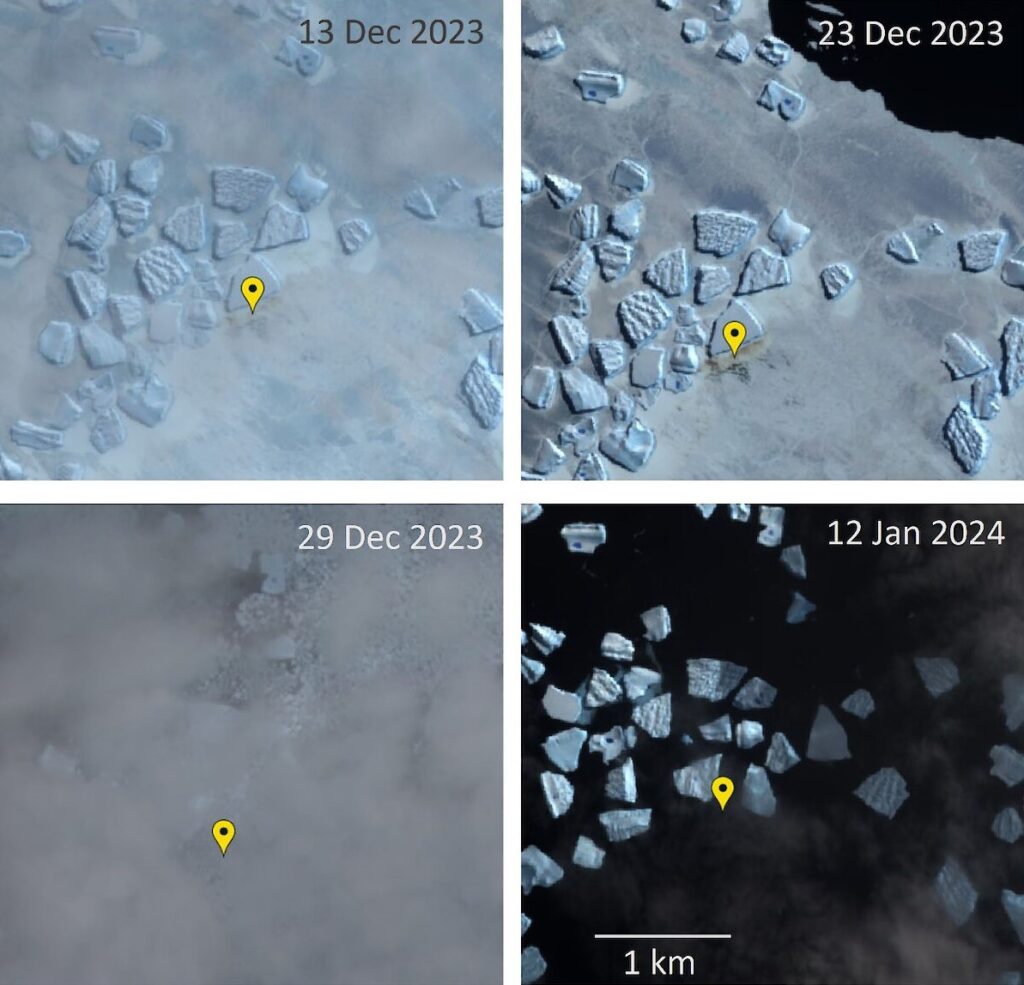

Dr Wienecke, sea-ice scientist Dr Jan Lieser, and seabird experts Dr Julie McInnes and Jonathon Barrington, used the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Sentinel-2 satellite imagery to look at changes in breeding habitat and ice conditions from 2018-23.

“Satellite imagery is a very useful way to determine the local and regional variability in fast-ice habitat,” Dr Lieser says.

“From this, we can assess the adaptability of emperor penguins to rapid change and the impact of habitat change on breeding success.”

The team examined satellite images covering 6000 km of the East Antarctic coastline between September and December each year — the time for chick rearing and fledging.

The team manually recorded colony locations each year and the distances between colonies and the nearest fast-ice edge.

Adults need to be close enough to the fast-ice edge to access open water for feeding. But being too close endangers breeding success if the ice breaks up before the chicks are able to survive at sea, according to the Antarctic Division.

“Thirteen of the 27 colonies we studied across East Antarctica are at risk of reduced or complete breeding failure, due to habitat loss, and nine of these 13 colonies experienced reduced or complete breeding failure at least once during the six years of the study,” Dr Wienecke says.

One colony disappeared but individuals may have joined other colonies, according to the division.

It says some colonies moved to new kinds of habitat, including ice shelves and ice tongues but these areas can be negatively affected by iceberg calving events that alter local conditions.

She says the new study shows medium and high-resolution satellite imagery is a useful tool for monitoring emperor penguin colonies and fast-ice habitat.

“Ongoing Antarctica-wide monitoring is essential to quantify the impact of changing fast-ice conditions on emperor penguins and the cumulative impacts of other threats such as disease,” Dr Wienecke says.

“Satellite imagery enables us to identify the locations of emperor penguin colonies each year, and assess the local environmental conditions, which is critical to understanding the consequences for individual colonies.”

WHAT IS FAST ICE?

Fast ice is sea ice that is attached to the Antarctic coastline, shoals, or grounded icebergs, the division explains. It acts like a discontinuous belt around the Antarctic coast and can remain in place for multiple years. It provides habitat and breeding grounds for emperor penguins and Weddell seals. It contrasts with ‘pack ice’, which is not attached to land. Pack ice drifts with winds and currents and constantly changes.